Which sounds better: a glass half empty or a glass half full? Logic will tell you that either way you look at it, the glass holds the same amount. But half full just sounds better, right? Unfortunately, in our minds, logic can sometimes be usurped by unconscious, cognitive biases that impact every part of our lives. These cognitive biases, or mental shortcuts, are our brain’s way of improving our lives by streamlining our decisions, but they can also trick us into making hasty, uninformed choices. And when you’re in the pits of litigation, “hasty” and “uninformed” are two adjectives you want to keep far away from your case.

The glass half full / half empty example is a demonstration of a cognitive bias known as the framing effect. The framing effect was first identified in the early 1980s by Israeli researchers Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky[1] and describes how an individual’s perception of a situation can change depending on the way that the situation is presented.[2] In their research, Tversky and Kahneman explained the framing effect through what they coined, the “prospect theory”: that when making decisions, people prefer options framed as gains over options framed as losses, even if the options are substantively identical.[3] Their research found that the framing effect is powerful, with framed losses on average being at least twice as psychologically influential in our decision-making as framed gains.[4]

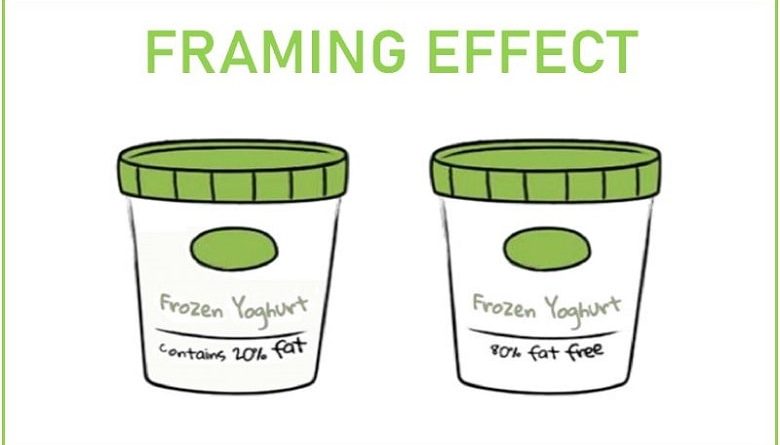

To demonstrate the framing effect, let’s look at an everyday example. Say you’re in the meat section of a grocery store. You walk up to the cooler and see a pound of meat labeled 30% fat. Right next to that package is another pound of meat labeled as 70% lean. If you’re looking for a healthier option, which one sounds healthier? The 70% lean meat has the exact same fat percentage as the 30% fat meat, but the label has presented the meat with more appealing language by putting the lean percentage on display. This makes the 70% lean meat seem healthier and thus a consumer “gain.” A brilliant marketing scheme that we see all the time.

So, sure, the framing effect exists in the grocery store as a marketing tactic. What does that have to do with litigation? Well, when you think about it, what is litigation but marketing for your case? When presenting your case to a judge, jury, or even to your client, the language you choose and the way you frame your case has significant influence. By framing unfavorable facts in a positive way, attorneys can persuade even skeptical listeners to award their client a favorable outcome. However, litigation is risky because your opposition has the same framing tactics available to them, and will use them to paint your client, and your case, as badly as they can. This means that the framing effect can create a precarious environment for even the strongest case.

It’s no secret that litigation is risky, but you only would take a case to trial if you were confident of a positive outcome, right? Not necessarily. Framing has been noted as a prime reason for out-of-court settlement failure.[5] Because of the framing effect, many cases that should have been settled often proceed to trial regardless of outcome confidence.[6] In 1996, Law Professor Jeffrey Rachlinski conducted a study in which half of the subjects, the “claimants,” could either accept a settlement of $200,000, or proceed to court where they would stand a 50% chance of being awarded $400,000.[7] The other subjects, the “defendants,” could pay $200,000 to the claimant immediately, or continue to court and risk a 50% chance of being ordered to pay $400,000. Rachlinski found that 77% of the claimants were happy to take the settlement, but only 31% of defendants were happy to pay it, choosing instead to proceed to court for the chance of not having to pay anything.[8] These results demonstrated that claimants were more risk averse when faced with a guaranteed gain versus a chance at a greater gain, while defendants were more risk-seeking when faced with a certain loss of $200,000 versus a chance to pay nothing.[9] Rachlinski’s study also identified a striking persistence of this trend across every level of outcome probability and risk-stakes, noting that defendant subjects were still much less willing than plaintiffs to accept a settlement offer even when they only had a 30% chance of winning at trial.[10] This research demonstrates that, overall, defendants are comfortable with extreme risk when framed with any chance at a positive outcome, no matter how slim the chances are. And this mindset can spell disaster for a weak case that would have been better settled.

No one likes to lose. Especially in the law, our common goal is to avoid loss and maximize gain for ourselves and our clients. But even though we all like to assume that we could spot the difference between a good opportunity and an unnecessary risk, framing can create misconceptions about facts, and blur the line between risk and reward. This mirage of framing can lead cases into trial when they otherwise should have settled, or even stall settlement conversations altogether.

With Resolutn you can find the middle ground in the framing mirage with a cutting-edge double-blind negotiation system and a neutral environment designed to maximize settlement success. Resolutn’s design also mitigates the loss-based framing effect of traditional settlement and instead rewards you for positive action so that more work can get done, faster.

Don’t be tempted by the framing mirage. Get started with Resolutn and find out for yourself what settlement can look like.

[1] See Amos Tversky & Daniel Kahneman, The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice, 211 Science 453 (1981) (accessed at https://www.uzh.ch/cmsssl/suz/dam/jcr:ffffffff-fad3-547b-ffff-ffffe54d58af/10.18_kahneman_tversky_81.pdf).

[2] Ian K. Belton, Mary Thomson, & Mandeep K. Dhami, Lawyer and Nonlawyer Susceptibility to Framing Effects in Out-of-Court Civil Litigation Settlement, 11 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 578 (2014).

[3] Why Do Our Decisions Depend on How Options Are Presented to Us?, The Decision Lab https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/framing-effect (last accessed November 11, 2022) (citing Amos Tversky & Daniel Kahneman, The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice, 211 Science 453 (1981)).

[4] Tversky, supra note 1; Natalie Cargill, Loss Aversion, Framing Effects, and Out of Court Settlements, LinkedIn (Jan. 13, 2015) https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/loss-aversion-framing-effects-out-court-settlements-natalie-cargill?trk=portfolio_article-card_title.

[5] Cargill, supra note 4.

[6] Cargill, supra note 4; Jeffrey J. Rachlinski, Gains, Losses, and the Psychology of Litigation, 70 Cornell Law Faculty Publications 114 (1996).

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Rachlinski supra note 5.